$25-million donation from Murray and Cara Sinclair to university will impact cancer research, treatment

Murray and Cara Sinclair have gifted Queen’s Health Sciences $25 million, which will be used to establish a cancer imaging facility and develop a biomanufacturing facility that will allow for cell-based therapies to be used locally in both research and treatment.

The gift, described as one of the largest donations ever made to Queen’s Health Sciences, was announced during a ceremony on Monday in the atrium of Queen’s University’s School of Medicine.

Patrick Deane, Queen’s University principal and vice-chancellor, told those in attendance that the Sinclairs’ generosity brings researchers a step closer to a cure for cancer.

“I think we’re all positioned to have increased hope,” Deane said. “Queen’s having a role in finding a cure for cancer is not really a question at all, because today’s announcement makes clear that our researchers are in the vanguard of cancer research, not just in Canada but in the world, and through this announcement, they will have unprecedented support to continue their groundbreaking work.”

Deane said the gift will have “an incredible impact on not only cancer research but also on how we deliver cancer care.”

“Their investment will help Queen’s researchers discover new potential treatments, test new drugs and better understand the value of treatment for patients,” he said.

The donation also precipitates the renaming of the Queen’s Cancer Research Institute to the Cara and Murray Sinclair Cancer Research Institute, also to be known as the Sinclair Cancer Research Institute, which School of Medicine dean Dr. Jane Philpott was “delighted” to announce.

Queen’s University’s Dr. Annette Hay is the senior investigator for the Canadian Cancer Trials Group and a hematologist and clinician-scientist with Kingston Health Sciences Centre. She was a panelist during a short discussion on stage on Monday to explore the potential impacts of the Sinclair family’s donation.

She described the gift as creating the infrastructure to have a significant impact not only for patients in Kingston but across Canada.

“This is a really big deal locally, and that will be felt nationally,” Hay told the Whig-Standard in an interview.

Hay works with patients who have blood cancers and utilizes treatments like chemotherapy and stem cell transplants, as well as conducting research in clinical trials testing new cancer treatments.

She said the donation will “deliver now and for many, many years to come.”

“The various areas where it will help include clinical cancer research of all types, understanding how cancer works, how cancer occurs, how the treatments work or don’t work — the whole span, including supporting students and the various aspects that go into cancer research.”

One of the new facilities slated will allow the local manufacturing of CAR (chimeric antigen receptor) T cells for use in CAR T cell therapy, which sees immune cells taken from a patient’s body and then engineered to fight specific cancer cells.

“It is a new treatment for cancer that works, and we have been using it for patients here for probably about four years now,” Hay said. “At first, patients who needed it actually had to go to the United States to get treatment because it wasn’t available in Canada. Then we’ve been gradually building capacity in Canada.”

Currently, patients who need this type of immunotherapy can access it in Toronto or Ottawa.

Still, the cell manufacturing largely takes place in the United States.

“What it means is we take a patient with cancer — and it’s only certain types of leukemias and lymphomas — and we actually remove their own immune blood cells in a safe outpatient procedure,” Hay explained. “(The cells) get flown down to the United States (to a) manufacturing facility in California or in New Jersey. There, the patient’s own immune blood cells are engineered to make them recognize their own cancer, and they’re flown back to Canada where they’re given to the patient.”

The approximately four-week delay that process requires can affect patient outcomes, Hay said.

“If you have a really aggressive cancer, that’s a problem,” she said. “Some people just can’t survive for weeks. It’s also super expensive, around half a million dollars for a dose for one person.”

Hay believes the new facility in Kingston will be able to complete this cell manufacturing faster, and cheaper.

“And then we can also continue to test new types of cell therapies that may work better, and may be safer, in clinical trials,” she said.

Hay said the donation is helping to establish a brand-new cancer treatment and research ecosystem in Canada.

“It’s going to benefit the most important people: the patients with cancer who need this,” she said. “People in our region will have increased access to clinical trials. But the impact is way more, because the results are intended to inform further research and patient care all across Canada, and around the world.”

The Sinclairs’ gift will also help to establish a new imaging facility under the direction of Dr. Paul Kubes, who is relocating to Kingston from Calgary and stepping into a new role as the Canada Excellence Research Chair in Immunophysiology and Immunotherapy.

During the panel discussion on Monday, Kubes described cancer treatment development in fishing terms.

“I’m a really bad fisherman,” he told those assembled. “I throw my lure in and I hope it works, but I can’t see what’s going on under the water. And I think that in cancer we have a similar problem. We make these T cells and we hope they get to that site and we hope that they work and we hope they kill the tumour. And sometimes they don’t, and we don’t understand why.”

With cutting-edge microscopic technology, Kubes is hopeful that he and researchers will be able to “actually go right inside the body and look at what the different cells are doing inside any particular organ.”

“We’re trying to understand how we might be able to treat cancers by engaging the immune system, by getting the immune system to say, ‘Look, this is a bad

In an interview Kubes described many cancer treatments as a “kind of lottery,” where treatment is given and then “they hope for the best.”

With new imaging techniques Kubes hopes to utilize, researchers could potentially answer the question of why or why not cancer treatments are working.

“The imaging tells us if we’ve done the right thing and now the immune cells don’t like the cancer and are starting to destroy it,” he said. “Or no, it didn’t work, and why didn’t it work? Can we use a different approach? Can we tweak the approach to make it work. Right now, we’re sort of working blind.”

The imaging will work in conjunction with current and future therapies.

“We’ve developed a way of looking under the water and being able to see what the fish are eating and now use the right lures,” he told the audience on Monday, coming back to the fishing analogy. “And so by the same token, as we develop our imaging in immunotherapy, we’ll be able to track these immune cells … that way we’ll be able to understand which immunotherapy works and which immunotherapy doesn’t work.”

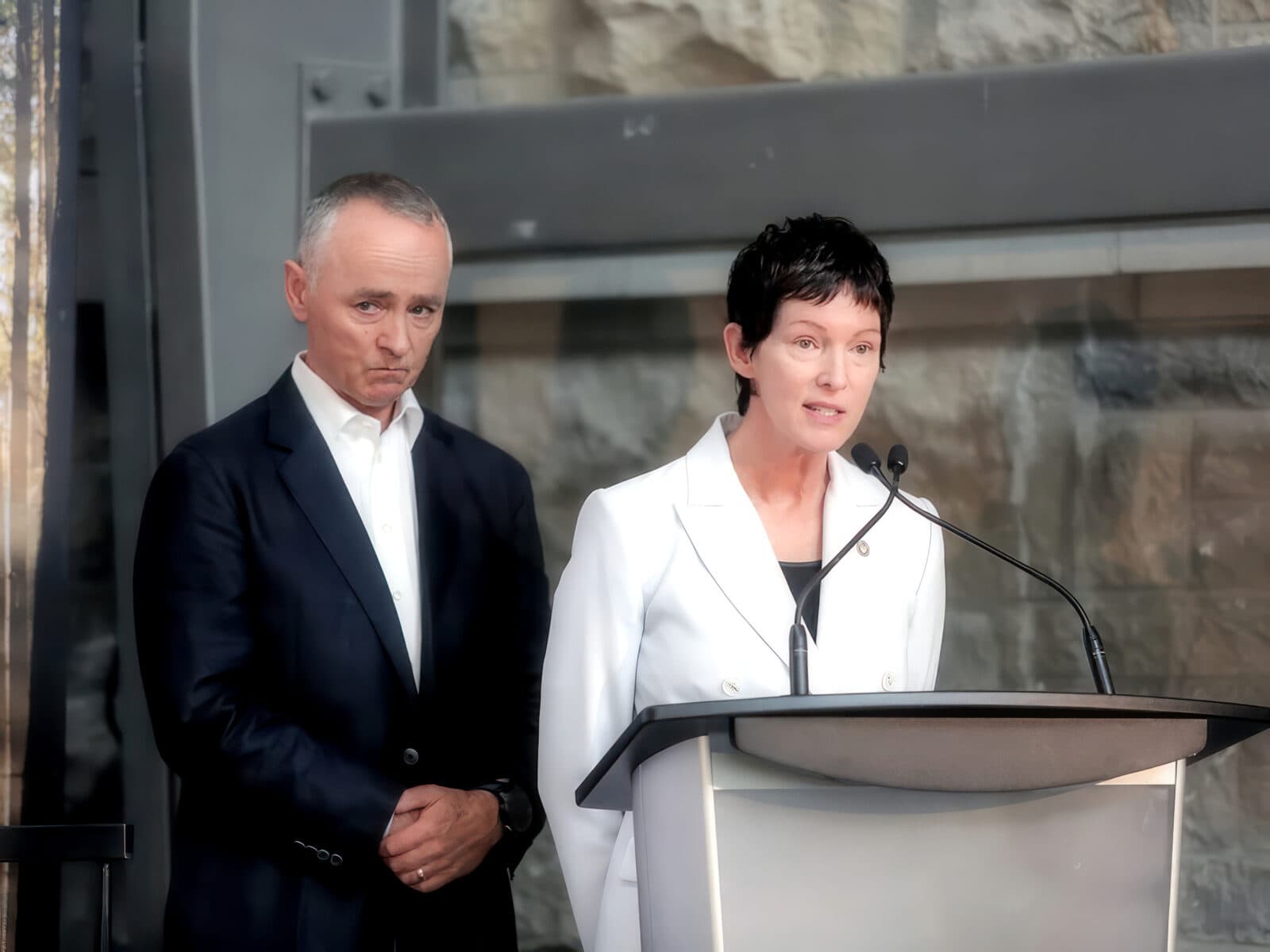

Donors Murray and Cara Sinclair, who live in Vancouver, attended the event on Monday and spoke about their decision to donate their gift to Queen’s University.

“Cancer touches us all,” Murray Sinclair told the Whig-Standard during an interview late last week. “They say 45 per cent of us will get a cancer diagnosis in our lifetime, and 675 people are diagnosed with it each day. My wife’s parents had cancer at different times and my father had cancer.”

Sinclair, a Queen’s alumnus, told those assembled on Monday morning through tears about his brother’s recent death due to a glioblastoma brain cancer diagnosis.

“Cancer crosses all lines, all cultures, race and religion, but its universality is what we can bring home,” Cara Sinclair, originally from Kingston, said on Monday. “It affects everyone, everywhere, so it can also bring us together to beat it.

“Because cancer affects all of us, we have a common goal. We all have a take in it and we understand how critical it is to act. We are all touched by cancer, and because of that, we can find the collective strength and motivation to do something about it.”

“We know that’s why everyone has joined us here today, to do something about it,” Murray Sinclair said. “For us that means honoring the memory of my brother and all the others we have lost to this terrible disease. It also means bringing people and the best minds together. It means supporting the groundbreaking research that is happening right here at Queen’s.”