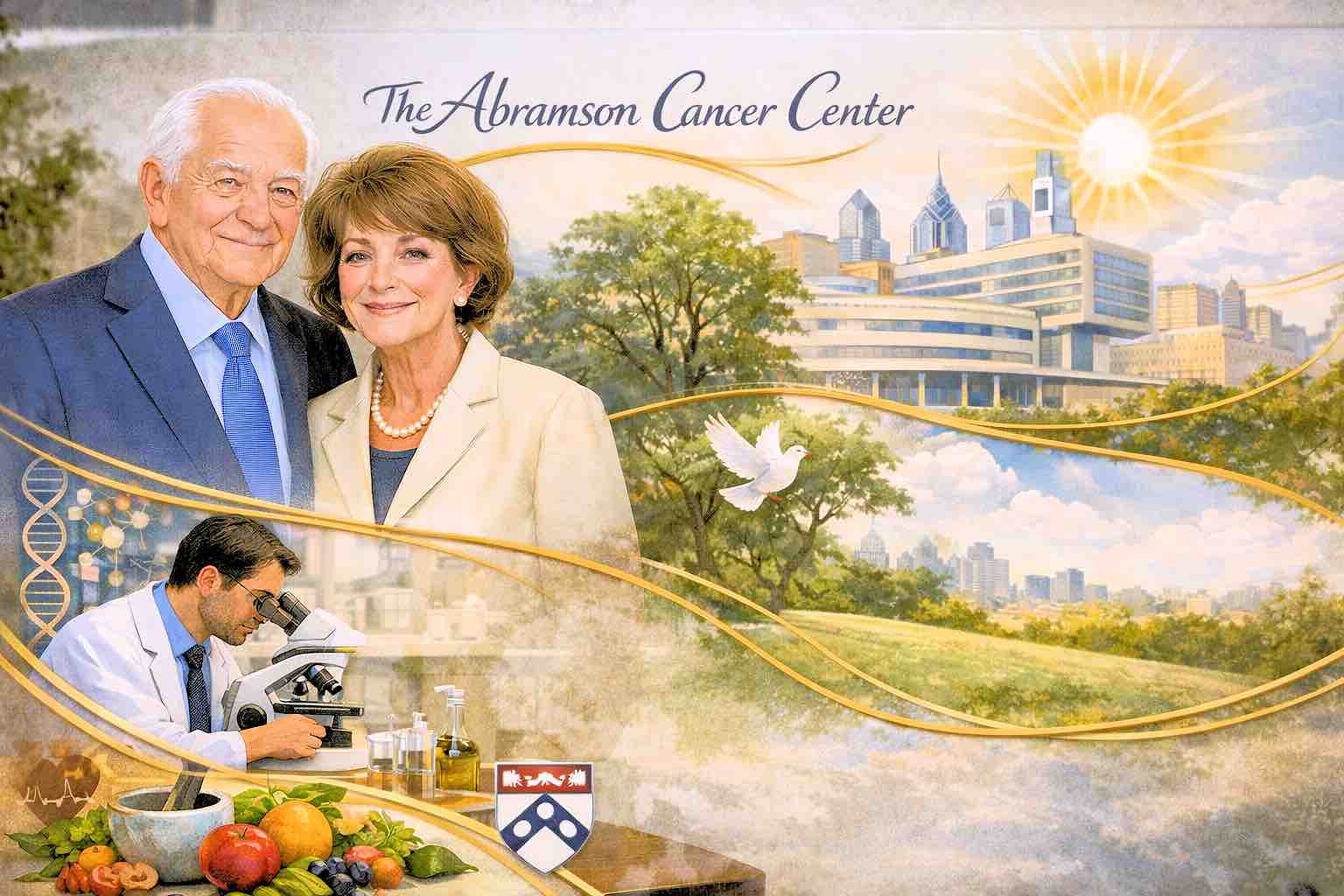

$100 million gift from the Arbramson family tackles holistic cancer care

Leonard and Madlyn Abramson’s landmark 100 million dollar gift to Penn Medicine has become one of the most consequential bets in cancer philanthropy, seeding a model of holistic care that is reshaping how a major academic center thinks about every patient and family it serves.

Leonard Abramson remains actively engaged, and he and Madlyn have three adult daughters — Marcy Abramson Shoemaker, Nancy Abramson Wolfson, and Judith (Judy) Abramson Felgoise — along with multiple grandchildren who are closely involved in the family’s philanthropic orbit, helping to carry forward the vision that first inspired the gift.

The Abramson Cancer Center that bears their name has evolved into a living expression of Madlyn Abramson’s conviction that world‑class oncology must treat the whole person — mind, body, and spirit — not just the tumor, embedding social workers, psychiatrists, nutritionists, and a broad web of supportive services alongside cutting‑edge science.

When Leonard and Madlyn Abramson, both deeply engaged in health care and philanthropy, made their 100 million dollar commitment, it ranked among the largest gifts ever given to a cancer center and one of the largest donations in the University of Pennsylvania’s history.

The gift established what was then the Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute, explicitly designed to integrate laboratory discovery, clinical innovation, and patient care in a single ecosystem, rather than treating research and treatment as separate silos.

Madlyn, herself a cancer survivor, pressed Penn’s oncology leadership to build a center where patients would not feel like “cases,” but like full human beings whose fears, families, and futures were understood and respected.

That insistence helped secure funding not only for eminent scientists and clinicians, but also for social workers, psychiatrists, and nutrition specialists who could support patients through the emotional and practical turmoil of a cancer diagnosis.

Over time, the University of Pennsylvania formally renamed its cancer program the Abramson Cancer Center in recognition of the couple’s transformative investment and hands‑on engagement, noting that their generosity had “helped to transform the level of clinical cancer care and service excellence” delivered there.

Colleagues recall Madlyn Abramson as an unusually accessible benefactor who stayed close to the work on the ground, listening to patients and staff and advocating for changes that would ease both psychological and physical suffering.

The Abramson family has continued to support oncology at Penn, including later gifts to fuel cancer research related to emerging health threats, underscoring their belief that cancer care must adapt continuously to new challenges and evolving patient needs.

Within Penn, the original gift is still cited as the moment the institution’s ambitions in oncology were “put on a rocket ship,” allowing recruitment, program building, and facilities planning at a scale that simply would not have been possible through incremental fundraising.

That early decision to embed holistic care into the DNA of the center now looks strikingly prescient as cancer treatment increasingly shifts to outpatient settings, leaving families and caregivers to shoulder more of the day‑to‑day burden.

Penn Medicine has built around that founding vision a growing suite of supportive services that span mental health care, spiritual support, fertility preservation, social work, integrative oncology, and palliative care, all aimed at helping patients and their loved ones navigate the often overlooked dimensions of cancer.

Programs like the Paula A. Seidman Psychosocial Counseling Program provide tailored counseling, psychiatric evaluation, and support groups for patients and families, while newer psychosocial oncology clinics extend free mental health care to both patients and caregivers, recognizing that caregivers are a central part of a patient’s care team and often entirely unsupported.

Integrative oncology offerings — from acupuncture and massage to yoga, mindfulness, and art therapy — run alongside advanced treatments and clinical trials, reflecting an institutional belief that resilience, symptom management, and quality of life are as critical to outcomes as chemotherapy dosing schedules.

For families, the implications of this donor‑driven model are increasingly tangible as more treatment takes place outside hospital walls. Social workers and specialized oncology staff help patients and caregivers anticipate practical and financial challenges, connect them with resources, and support complex decision‑making as they move through cycles of treatment, remission, and, at times, end‑of‑life care.

Dedicated support groups and counseling services are available not only to those receiving infusions or radiation, but also to spouses, adult children, and other loved ones wrestling with anxiety, grief, and the logistics of caregiving while balancing jobs and other responsibilities.

These services aim to reduce the emotional distress and economic strain that can derail even the most carefully planned medical regimen, acknowledging that adherence and healing are shaped as much by a family’s psychological and financial stability as by any single drug or device.

In this way, Penn’s holistic framework turns the Abramsons’ original thesis — that cancer care must reach beyond the disease itself — into a systemwide operational priority.

Within the broader landscape of cancer philanthropy, the Abramsons’ gift stands out not only for its size, but for the way it hard‑wired patient‑centered, holistic care into a major academic center at a time when many large oncology investments were focused almost exclusively on labs and bricks‑and‑mortar facilities.

Subsequent megagifts to cancer programs across the country have tended to emphasize drug discovery, precision oncology, or marquee buildings, while Penn’s Abramson Cancer Center has become a leading example of how early donor vision can institutionalize psychosocial and spiritual care as core, rather than ancillary, elements of oncology.

As Penn Medicine expands initiatives like psychosocial oncology clinics and integrative services across its health system, leaders explicitly point back to the Abramsons’ “whole‑person” mandate, treating it not as an aspirational slogan but as an operational blueprint for what 21st‑century cancer care should look like.

For patients, families, and caregivers moving through the center today, the result is a care ecosystem where Madlyn Abramson’s belief in individualized, holistic support is felt not just in the center’s name, but in the daily experience of being seen, heard, and accompanied through one of life’s hardest journeys.